What if, instead of passing out a quiz, the teacher handed your class voting ballots for the next presidential election? Sure, it is technically multiple choice, but you definitely shouldn’t guess. You don’t have to worry about acing or failing, but your choice is one of many deciding factors towards the fate of your country. Would you study beforehand? Would you and your peers even take it seriously? With the presidential elections around the corner, the question has arose whether youth should have representation in government.

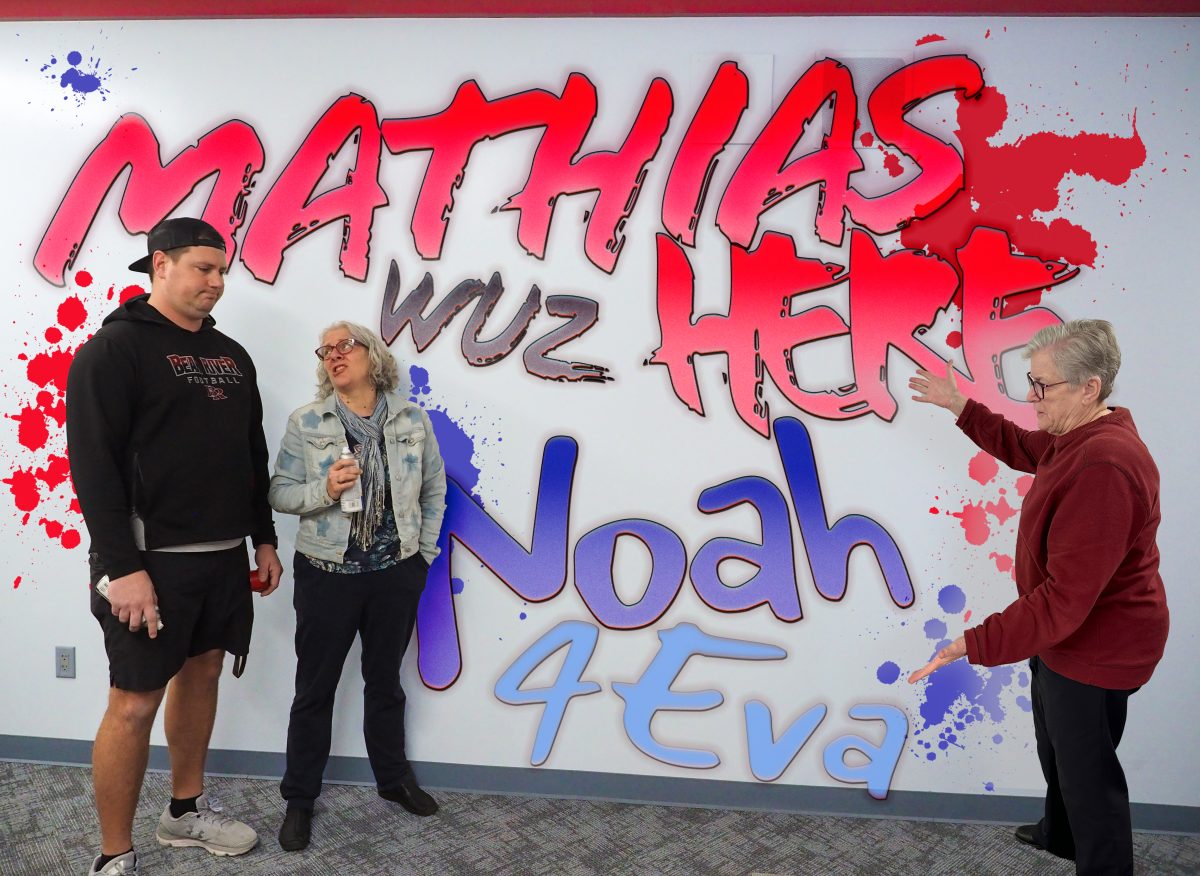

Representation in government has been a debated topic since this country was first cultivated on ideals of democracy. As AP U.S. History teacher Matt MacDonald noted, the extension of political representation to different social demographics has been a slow process.

“There have always been people left out of the political process,” he said. “For many, many years, it was white, rich, land-owning Americans [involved]. Then, it became universal, white, male suffrage where it didn’t matter if you owned property. Then, it became, as we got to the end of the 1800s, African Americans that are also going to have the right to vote. We are not going to discriminate based on race, which left women out. And then, women got the right to vote. And then, in the 60s and 70s, the big push was getting youth to vote, and we mentioned early with the Vietnam War, how that changed. If we’re gonna send these people to fight and die at 18, then we should lower the voting age to 18.”

But should we extend this right to teenagers? The first thing to consider is if it would even be necessary. Many believe that kids our age are not politically inclined enough to desire political representation even if it was offered to them. AP Government teacher Jeff Carrow voiced his frustrations while attempting political discussions in class.

“It just feels that, with 35 people and all the distractions that people have going on in their lives, that I get a few people that really want to be vocal and raise their hand and participate, … but it seems more challenging than ever to get the entire class engaged. And people are often in the middle of a discussion or inside conversation not directly related to the discussion. I try to use my energy to get people focused, but it’s a very challenging job.”

Mr. Carrow continued explaining how, in his opinion, not many students are politically driven.

“If you made me guess, somebody who has been teaching government most of his whole career, I would say somewhere in the vicinity of a third … of students are really engaged and really care about certain issues, leaving the other two-thirds which I would consider somewhat apolitical.”

Mr. MacDonald finds that students generally do care about politics, but they are only interested in the few issues that affect them directly.

“I feel like the trend right now is that a lot of our students have certain strong opinions on certain issues, and the issues that our students care the most are ones that come up a lot,” he said. “They are issues that affect them more in the short term. Nationally, healthcare is a major issue, and that is what a lot of voters say is on their mind. There is healthcare and social security and all of those things. But that doesn’t affect the students that we teach… The primary issue that affects them directly is minimum wage. That is always a good discussion because a lot of our students are working jobs at minimum wage… Another issue that comes up a lot is college affordability. That’s a big issue because our students are going to be going into college… Those are the issues I see us having the best conversations about.”

Mr. Carrow and Mr. MacDonald’s impressions of political passion within Bear River are reflected and opposed by the opinions of the student body. For instance, Senior Adam Merrill is interested in how political affairs will impact his life entering college.

“Seeing in the future how I’m going to go to college pretty soon and have to worry about debt which is a problem that is getting bigger and bigger every year, personally, I’m very invested in how our government deals with that.”

In addition to student debt, politics surrounding the First Amendment and freedom of speech are topics that Bruins find interest in. Senior Arieal Swindell explained its importance on campus and in the lives of students.

“The first amendment is really important because even though we are on school grounds, we still have our rights… And that shouldn’t be taken away just because we are in a public place of education, … especially in our AP Government class,” she said. “If we weren’t allowed to say what our beliefs and values were, then what is the point of that class and many others?”

But in addition to tangible political issues, some Bruins are also interested in the effect politics will have on people everywhere. Merrill continued by expressing his concern for policies that reach further than Nevada County.

“A lot of politics don’t necessarily affect me directly because I was born into a place where I have access to things like health care, and I don’t have to worry about a lot of financial things,” he said. “I mean, I was also born in America which itself is a pretty big privilege. And I understand that a lot of other people are not born into the position I was, and I want to make sure they are being treated fairly.”

With varying political passions, it only makes sense that there is no clear answer whether students believe youth should have representation in government or what their representation should look like. Sophomore Ryan Downs believed that younger students should not have the right to vote because they are still too impressionable.

“Maybe seniors, but freshmen and sophomores? I don’t think they should have representation yet because I guess some don’t really know how to think on their own yet. Some just look at their parents and just go with what they think,” he said.

Swindell, however, felt that youth should have their voices heard even if it is not in the form of a vote.

“I think they should. Even if it’s not a physical representation, there should be some sort of liason or some type of representative in government,” she said. “And if not a literal one, students need to be connected to the representatives of their states.”

Merrill believed that younger people should not be included in the political process but change should be carried out by politicians that have their interest in mind.

“I think that our politicians should be aware of the issues facing youth and should be working towards bettering those things, but I don’t think that having youth in the government would be the best idea because they just don’t have the experience and the knowledge that I think is required,” he said.

Returning to a teacher perspective, both Mr. Carrow and Mr. MacDonald wishes to instill passion into their students on political matters. Mr. MacDonald viewed it as an essential part of his job as an educator.

“The number one thing is just to try to get people to be passionate about an issue… that’s the best part of the process because we live in a very polarizing time,” he said. “And I feel like just getting people to find and identify what issues they really care about is probably the most important thing that, as teachers, I think we can do. It’s not so much about what side of the issue you are on, but it’s more so about how this issue is important.”

In terms of the youth’s impact, both teachers feel that students should have a voice. However, as Mr. Carrow explained, this voice can be achieved in a multitude of ways other than voting.

“We just read the story in the previous chapter about a girl who got very involved politically even before she could vote,” he said. “You can still get involved politically outside of voting at any age. You can volunteer, you can campaign, you can canvas neighborhoods, you can do polling, you can just have conversations. Freshmen, middle schoolers, anyone can get involved. So I guess there has to be a line somewhere where you can vote, and I’m relatively pleased with 18. But yes, you can go to board meetings, you can go to town hall meetings, so there are still avenues to get involved.”

MacDonald agreed that students should get involved in politics on the local level.

“I think the hardest part is defining what representation means,” he said. “… Certainly, I think at the local level, students can get more passionate about school issues, issues at our school or in our community. That’s a great way to start. And going to board meetings, getting into conversations about dress code or conversations about policy that’s being made at our school like bell schedule. Those are all ways we can practice democracy and involvement. And hopefully, that trickles down to the local and state and national level as they get older.”

I agree that 18 is a solid age to begin voting because it takes experience to craft your own well-informed political positions, and more notably, I feel like there is a great sense of apathy towards politics at younger ages.

There are many reasons for this lack of interest, but in my opinion, the main cause is the way politics are incredibly sensationalized in the media. Thinking historically, before elections were televised, information about politicians was either obtained directly from the source or read about in newspapers or reports. At this point in American history, the public knew their candidates on a less personal level. They were figures that were judged mainly by their statements during debates or speeches. Now, with the advent of social media, politicians are celebrities. A storm posts and tweets allow the people to know their candidates on an extremely casual level. This leads many, especially the youth, to lose respect for the political process in general because the government doesn’t seem to have the professionality or importance that it once did.